“He who holds Stirling, holds Scotland”. The quote refers to Stirling Castle, which was the center of Scottish history for centuries. The castle was all but impregnable, surrounded on 3 sides by nearly vertical rock cliffs with sweeping “I can see forever” views. The castle’s importance, however, was due to those sweeping views overlooking a bridge over the River Forth, the primary passage between the Lowlands and Highlands. Due to its strategic location and invincible fortifications, it was both a focus for conquest and a safe refuge for royalty. So much history occurred around this castle that I would be remiss not to mention some. I promise a rather quick sketch. In depth, the history reads like a trashy novel – victories, banishment, plotted returns, intrigues, murder, assassinations, a son waging war (and killing) a father, imprisonments, escapes, revolts, beheadings …. The kings led interesting, if short, lives. We won’t go there (much), though – just a bit of history of the castle. This will be a long post, so feel free to skip to the pictures that follow! However, I think the history provides very useful context.

Stirling Castle’s written history began in 843, when an historian noted that Kenneth MacAlpin, the first King of Scotland, besieged Stirling Castle during his successful fight to unite the Picts and Scots into the kingdom now known as Scotland. At some point it became the home of Scottish royalty; in 1110 King Alexander I dedicated a royal chapel there, and his successor King David I made Stirling itself a royal city. Skirmishes with England became common, and Stirling Castle was the football. In 1174 the Scottish King William I invaded England but was captured at Alnwick (Alnwick Castle, February 14, 2015); to gain his freedom he ceded Stirling Castle to English King Henry II. In 1189 he got it back when English King Richard I came to the throne. Then came the Wars of Scottish Independence, which lasted for 60 years. The outline below shows how the war centered around Stirling Castle. Notice how the castle ping-pongs between the two countries!!

1296 – Stirling Castle was captured by English King Edward I.

1297 – The Scot William Wallace (a.k.a. Braveheart) defeated a superior English force at the Battle of Stirling Bridge (within sight of Stirling Castle) and later that year took back the castle following a siege.

1298 – William Wallace was defeated at the Battle of Falkirk, and the English reclaimed Stirling Castle.

1299 – The English surrendered the castle to the Scots following a siege.

1304 – English King Edward I waged war on Scotland for years; Stirling Castle was the last stronghold; it was besieged and bombarded by 17 siege engines for 4 months. When a massive trebuchet was built (“War Wolf”) capable of hurling missiles weighing 300 lbs, the Scots surrendered and the English controlled it for 10 years.

1304 – English King Edward I waged war on Scotland for years; Stirling Castle was the last stronghold; it was besieged and bombarded by 17 siege engines for 4 months. When a massive trebuchet was built (“War Wolf”) capable of hurling missiles weighing 300 lbs, the Scots surrendered and the English controlled it for 10 years.

1314 – King of Scotland Robert the Bruce (Robert I) retook the castle by beating the 3X larger English army of Edward II at the Battle of Bannockburn just outside the Stirling Castle walls.

1336 – Stirling Castle was captured by the English

1337 – A siege of Stirling Castle by the Scots was unsuccessful

1342 – The future Scottish King Robert Stewart (Robert II) retook Stirling Castle in a successful siege. The castle remained Scottish until the end of the war in 1357.

Two of those battles, the victories of the plucky Scots under William Wallace in 1297 and Robert the Bruce in 1314, both against huge odds, remain a source of fierce pride in a Scotland that still questions its English union.

Before visiting the castle, a little more history (but 400 years worth!) is worthwhile. The Stewart kings Robert II and III made Stirling Castle their primary residence. It’s from Robert II’s time that the earliest surviving parts of the castle were built – the foundations of the North Gate, built in the 1380’s. King James I ascended the throne (then was caught and imprisoned by the English, saw a beautiful lady from his tower prison, wrote a poem about her [The King’s Quair] that we all read in high school, married her [cousin to English King Henry IV], and was released), but was assassinated in 1437, whereupon his queen smuggled son James II into Stirling Castle for safekeeping. James III was born in Stirling Castle and favored it as his “most pleasant residence” (he was killed in a revolt led by his son James IV). During the reign of James IV and V, 1490 – 1560 (and beyond), the city entered its golden age; Stirling became the principal royal center. Almost all the present buildings in the castle were constructed, in grand style, turning the castle into the showpiece of Scotland (i.e., one-upmanship over England). With James IV’s death, James V was crowned in the royal chapel of Stirling Castle (at age 17 months). He married the French noblewoman Mary of Guise and had a daughter Mary Queen of Scots. When James V died, Mary of Guise became Regent of Scotland; with nobles scrambling for power, she brought her daughter Mary to Stirling Castle for safekeeping behind strong walls (she came with 2,500 cavalry, 1,000 infantry, and a baggage train a mile long). Mary Queen of Scots was crowned (as an infant) in Stirling Castle and spent her early years there, subsequently going to France. In the face of threats from England, French troops were brought in and the outer defenses of Stirling Castle were built. Mary Queen of Scots returned to Stirling Castle, wed, and had a son there, James VI (responsible for the King James version of the Bible) in 1567. The Catholic Mary’s estranged husband was mysteriously murdered, she remarried, there was an uprising, and she was abducted to England and held captive by Queen Elizabeth I. With various factions plotting for power, Mary was forced to abdicate to James VI, who was crowned king at age 9 months, raised in the safety of Stirling Castle as Protestant, and turned against his Catholic mother. Stirling Castle became the base for James supporters, Edinburgh for Mary’s. Attacks were made against Stirling Castle, but failed. Mary was eventually executed by Queen Elizabeth I. When Queen Elizabeth died without an heir in 1603, King James VI of Scotland became King James I of a united Scotland and England. He left for London, returning to Scotland only once, briefly, after 14 years. With his absence, Stirling’s role as a royal residence declined, and Stirling Castle became principally a military center and a prison. When James VI died in 1625, the son Charles I inherited a kingdom divided by religion and throne pretenders. His efforts to impose English liturgy on Scotland led to war – and his beheading, with Scotland choosing son Charles II as their king, who lived in Sterling Castle in 1640, while England got Oliver Cromwell, who turned England into a Republic. Charles II marched against Cromwell and was defeated; Cromwell’s forces successfully besieged Stirling Castle in 1651, inflicting still-visible shot marks within the Castle. Charles II fled, but returned as King of England and Scotland a decade later when Cromwell died and the English monarchy was restored. Religious tension grew, and Charles’ attempted to introduce religious freedom for Catholics was unsuccessful. When Charles II died and his Catholic brother James VII (English James II) not only ascended the throne but subsequently produced a Catholic heir, war broke out; James, the last Catholic King of England and Scotland, was forced to flee in 1688 and Protestants (William and Mary) assumed the throne. James continued to claim the thrones of England and Scotland from exile in France and encouraged revolts in his name (Jacobite Rebellions). His grandson the Bonnie Prince Charlie led an ultimately unsuccessful uprising in 1745; the Bonnie Prince bypassed Stirling and captured Edinburgh, but returning to Stirling in 1746 he was unable to capture Stirling Castle. This was the last time that Stirling Castle was besieged. The Bonnie Prince’s subsequent defeat ended any chance of Catholicism becoming re-established in England.

Wow! A lot of history swirled around this castle. Let’s take a look at it (finally, eh?). This  picture is an artist’s impression of the grand entrance to James IV castle, based on a detail from a Scottish map done in the late 1500’s; the gate was among the most magnificent in the UK. When it was constructed, it both strengthened the castle’s defenses and projected the greatness of James himself. The gate was probably reached by wooden bridge over a moat. This original gate was higher than the current one; it had 5-story towers capped with conical roofs, and was probably coated in gold limewash, with carved details painted and gilded.

picture is an artist’s impression of the grand entrance to James IV castle, based on a detail from a Scottish map done in the late 1500’s; the gate was among the most magnificent in the UK. When it was constructed, it both strengthened the castle’s defenses and projected the greatness of James himself. The gate was probably reached by wooden bridge over a moat. This original gate was higher than the current one; it had 5-story towers capped with conical roofs, and was probably coated in gold limewash, with carved details painted and gilded.

The first detailed drawing of Stirling Castle comes courtesy of a military engineer in 1671, although the view is not from the gate.

The first detailed drawing of Stirling Castle comes courtesy of a military engineer in 1671, although the view is not from the gate.

Today the entrance to the castle – the old castle interior – looks like the illustration shown just below, with the buildings built by James IV and  V peeking above the wall. Comparing this picture with that from the 1500’s above, the current gate is clearly less grand and more military-looking, reflecting its changed role after the departure of James VI (and the impact of siege bombardments!).

V peeking above the wall. Comparing this picture with that from the 1500’s above, the current gate is clearly less grand and more military-looking, reflecting its changed role after the departure of James VI (and the impact of siege bombardments!).

The main entrance to Stirling Castle now takes you into the  extensive outer defenses, built by Protestant Queen Anne (daughter of deposed Catholic James VII) in 1708 after her half-brother contested the crown. This map of the Stirling Castle fortress shown on the left is a good overview. The original entrance to the castle, now called the “Forework”, is just below the center of the picture. The current entrance to the outer defenses is at the bottom left. That entrance is shown in the pictures below. The entrance takes you to a

extensive outer defenses, built by Protestant Queen Anne (daughter of deposed Catholic James VII) in 1708 after her half-brother contested the crown. This map of the Stirling Castle fortress shown on the left is a good overview. The original entrance to the castle, now called the “Forework”, is just below the center of the picture. The current entrance to the outer defenses is at the bottom left. That entrance is shown in the pictures below. The entrance takes you to a

courtyard holding pen, with another gate that takes you to the front of the original castle, shown below.  Turning left after going through that second entrance (the map of Stirling Castle, above, provides a useful overview), one comes to a formal garden/green called the Queen Anne Garden, shown below, although it was already there in the 1400’s for the royal family to enjoy. You can begin

Turning left after going through that second entrance (the map of Stirling Castle, above, provides a useful overview), one comes to a formal garden/green called the Queen Anne Garden, shown below, although it was already there in the 1400’s for the royal family to enjoy. You can begin

to see the amazing vista that the castle provides, so let’s take a look around. It’s

impressive, and many of the important battles of Scotland would have been visible from here. You will also note, from the map of the Stirling Castle above, that there are a number of cannon that look out over this vista; those cannon were instrumental in blowing up siege towers in later years.

OK, in we go through what used to be the grand entrance to the castle. It definitely looks more military than grand! The entrance takes us into the “Outer Close” – and mostly to a view of the back ends of the major buildings, the royal palace and the great hall, as well as going downhill to the “Great Kitchens” of the palace.

OK, in we go through what used to be the grand entrance to the castle. It definitely looks more military than grand! The entrance takes us into the “Outer Close” – and mostly to a view of the back ends of the major buildings, the royal palace and the great hall, as well as going downhill to the “Great Kitchens” of the palace.

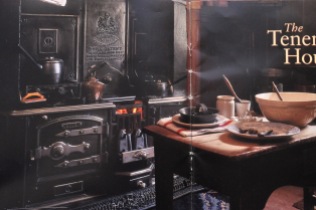

The Outer Close also had an interesting exhibit on the food of the late 1400’s – as you might imagine, it’s not too different from today.

The Inner Close was the core of Stirling Castle in the 1100’s and continued to be its center (the map of Stirling Castle is again useful). In its golden age it was surrounded by the trappings of royalty, consisting of the King’s Old Building (private apartments of James IV, 1496), the Great Hall (used for banquets and business, 1503), Royal Palace (built by James V for greater luxury and privacy, 1540), and Chapel Royal (built by James VI for the baptism of his first son, 1594). These buildings have been restored from their military conversions.

James V built the Royal Palace in grand style, on par with the finest French chateau, in order to impress and “proclaim the peace, prosperity and justice of his reign”. Here’s what the outside looks like today, and what it would have looked like in 1540:

James V decorated the outside of the palace with over 250 sculptures, including classic gods and goddesses, designed to promote his authority and demonstrate his right to rule. The statues have weathered (and suffered indignities) over the centuries, but they were clearly nicely done; examples below. The last picture shows how they would have looked back in the day.

The Great Hall of 1503 was by far the largest banqueting hall ever built in medieval Scotland. Two high windows lit the dais on which the king and queen sat. Five enormous fireplaces provided heating. A hammerbeam roof soared above. It was a grand setting for

the sumptuous banquets of the Renaissance kings, and in particular the two royal baptismal celebrations for the sons of Mary Queen of Scots and James VI. In the latter,  the fish dish came on a model ship 15′ long and 36′ high, with a salvo of 36 brass guns. As you can see from the picture of the Great Hall interior, above, to us the Great Hall really just looked like a big, empty building; it needed the pomp and glitter of tables and tapestry and roaring fires (and roaring cannon) to be impressive.

the fish dish came on a model ship 15′ long and 36′ high, with a salvo of 36 brass guns. As you can see from the picture of the Great Hall interior, above, to us the Great Hall really just looked like a big, empty building; it needed the pomp and glitter of tables and tapestry and roaring fires (and roaring cannon) to be impressive.

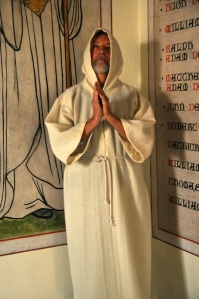

The Chapel Royal, one of the first Protestant churches built in Scotland, was built for that same baptism for the son of James VI (1594). The painted frieze in the interior survives from Charles I’s coronation visit to Scotland in 1633.

The King’s Old Building, at the castle’s highest point, was built by James IV for his private residence; the turreted staircase went to his apartment, with spectacular views. The building has endured 500 years of alterations; the right picture is an artist’s concept of what it might have looked like in the 1500’s.

Attached to this building is the Stirling Heads Gallery housing the (fabulous) original carved portraits in oak that decorated the King’s Presence Chamber (a meeting room for honored visitors) in the Royal Palace. The carvings were taken down following a ceiling collapse in 1777, and of a possible 100 original heads, 38 survive. They’re beautiful – and they’re not small, about 3 feet across. They’re divided into themes: heads of royalty (and the right to rule), “worthies” – heroes from history and myth, heads from Roman emperors, courtiers and costume, and Hercules. We’ll share a bunch, starting off

with Royalty. The heads below show courtiers wearing the (carefully depicted) fashionable

clothes of the 1540’s. A few “worthies” are shown below, and Hercules below that.

Finally, these heads were recovered with traces of paint on them. It is thought the heads were vibrantly painted, as you’ll see in more detail when we show you their reproductions in the King’s Presence Chamber (shortly). For now, let’s give you a flavor for what the heads really looked like!

To complete our visit to the Inner Close, we’ll tour the Royal Palace apartments. To mark the arrival of his (2nd) French wife, Mary of Guise, James V built the Royal Palace to be as fine a residence as Mary would have known in the richer kingdom of France. Both interior and the exterior were painted in bright colors with plenty of gilding to overwhelm with flamboyance. The 6 rooms open to the public are the king’s and queen’s apartments. Each had three spacious rooms – in ascending order of privacy: an Outer Hall‚ an Inner Hall and a Bedchamber. Access to these rooms was restricted according to the importance of the visitor. The rooms were on  the same floor, arranged around a courtyard known as the Lion’s Den, and were used for a variety of purposes – taking meals, greeting important visitors, meetings on affairs of state, and dancing and entertainment. The bedchambers were rarely used for sleeping; the king and queen slept in small private chambers known as closets.

the same floor, arranged around a courtyard known as the Lion’s Den, and were used for a variety of purposes – taking meals, greeting important visitors, meetings on affairs of state, and dancing and entertainment. The bedchambers were rarely used for sleeping; the king and queen slept in small private chambers known as closets.

We’ll start with the King’s Outer Hall, shown above. With sufficient social standing, you would be admitted to this hall to wait for a possible audience with the king. It was a great honor to be admitted to the King’s Inner Hall, or “Presence Chamber”, shown below.

You only made it to the King’s Bedchamber (left picture) if you were really important, or a personal friend. The king probably dressed, washed and prayed here.

You only made it to the King’s Bedchamber (left picture) if you were really important, or a personal friend. The king probably dressed, washed and prayed here.

The Queen’s Outer Hall (below) was also a waiting room,

and it was a similar honor to be invited to her Inner Hall, shown below.

The low stools in the first picture were for the Queen’s ladies in waiting. The ceiling may also have been covered in carved heads. Finally there is the Queen’s bedchamber, reserved  for the queen and her most important visitors. The bed was symbolic; she slept in a small room nearby.

for the queen and her most important visitors. The bed was symbolic; she slept in a small room nearby.

Perhaps you noticed the tapestries in the Queen’s Inner Hall? Like the one over the fireplace, above? They’re gorgeous and vivid! Tapestries were extremely expensive and were prized by the wealthy elites of the European Renaissance. It is known that James V had two sets of tapestries featuring unicorns, and historians of James IV believe the royal collection included tapestries similar to the famous The Hunt of the Unicorn series from 1500. Accordingly, to furnish the Queen’s Inner Hall as it would have looked in the 1500’s, Stirling Castle is re-creating the 7 tapestries that constitute The Hunt of the Unicorn using traditional hand-weaving techniques, the weaving being done at the castle. Six of them are on the walls now, but before we show some of them to you, we need to show you how the 7th one is being (painstakingly!) made.

Getting to where the tapestry is being weaved takes us to the North Gate, the oldest part of the castle. The road there provides a nice overview of the surrounding land as well as the

ancillary buildings of the castle (site of the weaving). The gate itself does indeed look old;

it was part of a gatehouse built in 1381. Looking back at the North Gate, below, it is not known how the upper  part originally looked; the upper regions were leveled in 1511 to provide kitchens for the Great Hall.

part originally looked; the upper regions were leveled in 1511 to provide kitchens for the Great Hall.

Walking into the tapestry weaving room, we were unprepared for the scale of the enterprise. The tapestries are fabulous on the wall, but we didn’t think about the intricacies of their creation. It was fascinating, and we hope you’re impressed by the pictures below. There was only one weaver when we were there, but several are involved. They wear noise-cancelling headphones, and you are not allowed to distract them. A separate person is available to answer questions (and enforce the rules).

Now that you’ve seen the scale, back to the Queen’s Inner Hall and the finished tapestries! The tapestry below is one of our all-time favorites that we’ve seen in books, and it was a delight to see it in real life – a copy for sure, but a copy that probably can not be surpassed.

Another one; we love the detail – look, for instance, at the waves in the water.

We’ll do one more.

Finally we’ll tour the castle kitchen. As shown in this schematic, it was divided into a cooking area, a prep area, and a baking area. Almost all the kitchen staff were male, while women worked as “hen wives” or “alewives”. Brewing ale (from barley) was usually the work of women, done within the castle, and ale was consumed with every meal – even by children, as it was safer to drink than water or milk. It was also highly nutritious and an important part of the medieval diet. Much of it had a low alcohol level. A servant working for the royal family was given a daily allowance of about 2 quarts.

Finally we’ll tour the castle kitchen. As shown in this schematic, it was divided into a cooking area, a prep area, and a baking area. Almost all the kitchen staff were male, while women worked as “hen wives” or “alewives”. Brewing ale (from barley) was usually the work of women, done within the castle, and ale was consumed with every meal – even by children, as it was safer to drink than water or milk. It was also highly nutritious and an important part of the medieval diet. Much of it had a low alcohol level. A servant working for the royal family was given a daily allowance of about 2 quarts.

The pictures below show the kitchen in order, moving from the cooking area to the bread

ovens. Those of the upper crust of Stirling Castle – and their servants – enjoyed fine white bread from wheat flour, sieved through woolen and linen cloth to remove the bran. Most people had coarser flour from rye or barley, with darker and heavier loaves.

There was a decided (social) food train. The king and queen were served all of the food first, the extra then passed on, in order, to the courtiers, various officials, their personal servants, and finally those who served the food to the tables. The same system applied among the other servants.

Yep. I know. This was a loooong post, but Stirling Castle had a lot of meat on its bones! The next posts will be (gorgeous) scenery, not history, so you get a break! We’re off to the Highlands, to Oban on Scotland’s west coast.

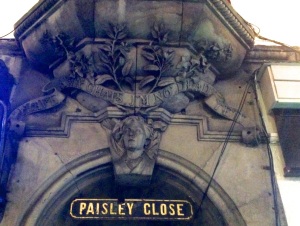

This house, the oldest in Glasgow, was built by (and near) the Glasgow Cathedral in 1471. It likely reflects “the lifestyles of the rich and famous” for that time. It was originally the home of one of the 32 canons who managed a part of the Cathedral’s vast diocese – in this case the land at Provan (the other 31 canons were similarly housed). By the 1600’s it had become a private home; by the 1700’s, and for the next 200 years, it was used as an inn, with rooms on the upper floors and a wide range of shops on the ground floor. A small extension housed the city’s hangman. It’s a pretty cool place, all stone with massive, rough-hewn, low-hanging beams and fireplaces everywhere. The entrance opens into the

This house, the oldest in Glasgow, was built by (and near) the Glasgow Cathedral in 1471. It likely reflects “the lifestyles of the rich and famous” for that time. It was originally the home of one of the 32 canons who managed a part of the Cathedral’s vast diocese – in this case the land at Provan (the other 31 canons were similarly housed). By the 1600’s it had become a private home; by the 1700’s, and for the next 200 years, it was used as an inn, with rooms on the upper floors and a wide range of shops on the ground floor. A small extension housed the city’s hangman. It’s a pretty cool place, all stone with massive, rough-hewn, low-hanging beams and fireplaces everywhere. The entrance opens into the the unconquered north, in AD 142 Hadrian’s successor Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered a new wall built about 70 miles further north of the existing wall. Again these clever Romans somehow knew where the shortest distance would be, and the wall was built from the river Clyde just above present-day Glasgow to the Firth of Forth just west of present-day Edinburgh. The wall was 39 miles long, about 13 feet high, and 16 feet wide; it took 12 years to complete. It was built of turf and earth on a stone foundation. Like Hadrian’s Wall it had a deep ditch on the north side and a military road on the south. A wooden palisade is thought to have been on top. It was protected by 17 forts with about 10

the unconquered north, in AD 142 Hadrian’s successor Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered a new wall built about 70 miles further north of the existing wall. Again these clever Romans somehow knew where the shortest distance would be, and the wall was built from the river Clyde just above present-day Glasgow to the Firth of Forth just west of present-day Edinburgh. The wall was 39 miles long, about 13 feet high, and 16 feet wide; it took 12 years to complete. It was built of turf and earth on a stone foundation. Like Hadrian’s Wall it had a deep ditch on the north side and a military road on the south. A wooden palisade is thought to have been on top. It was protected by 17 forts with about 10 “fortlets”, very likely on (Roman) mile spacings. In spite of the effort it took to build the wall, it was abandoned only 8 years after completion (162 AD), the garrisons being relocated back to Hadrian’s Wall. Following a series of attacks in 197 AD, the emperor Septimius Severus arrived in Scotland in 208 to secure the frontier. He ordered repairs and re-established legions at Antonine’s Wall (after which the wall also became known as the Severan Wall). Only a few years later the wall was abandoned for the second time and never fortified again.

“fortlets”, very likely on (Roman) mile spacings. In spite of the effort it took to build the wall, it was abandoned only 8 years after completion (162 AD), the garrisons being relocated back to Hadrian’s Wall. Following a series of attacks in 197 AD, the emperor Septimius Severus arrived in Scotland in 208 to secure the frontier. He ordered repairs and re-established legions at Antonine’s Wall (after which the wall also became known as the Severan Wall). Only a few years later the wall was abandoned for the second time and never fortified again.

art (stained glass, tapestries), Egyptian, Islamic and Chinese art, French Impressionist paintings, sculpture, armor, architecture, furniture…. Be prepared for ecclectic! So where to start, eh? How about this vase, found in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, from 100-200 AD (restoration in the 1700’s). Fill it with wine and take a bath?

art (stained glass, tapestries), Egyptian, Islamic and Chinese art, French Impressionist paintings, sculpture, armor, architecture, furniture…. Be prepared for ecclectic! So where to start, eh? How about this vase, found in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, from 100-200 AD (restoration in the 1700’s). Fill it with wine and take a bath?

world. The 3 panels shown on the left came from a French cathedral from about 1280 (!), showing a wedding party in the center, with kitchen scenes above and below that referenced the trade guild that paid for the window. The only paint on the glass is a brown metal oxide that defines the faces, hair and folds of the clothes. The individual pieces of colored glass are small, and therefore the many lead canes holding them together made the panels strong. There are few restorations, and the window looks almost exactly like it did 750 years ago.

world. The 3 panels shown on the left came from a French cathedral from about 1280 (!), showing a wedding party in the center, with kitchen scenes above and below that referenced the trade guild that paid for the window. The only paint on the glass is a brown metal oxide that defines the faces, hair and folds of the clothes. The individual pieces of colored glass are small, and therefore the many lead canes holding them together made the panels strong. There are few restorations, and the window looks almost exactly like it did 750 years ago.

Our final look at a Mackintosh tea room is “The Willow TeaRooms and Gift Shop”. These rooms are not in a museum – they constitute a 1903 Mackintosh building that is still serving food and tea to the public. Below are pictures of these rooms as they looked in 1905;

Our final look at a Mackintosh tea room is “The Willow TeaRooms and Gift Shop”. These rooms are not in a museum – they constitute a 1903 Mackintosh building that is still serving food and tea to the public. Below are pictures of these rooms as they looked in 1905;