CHINESE SCHOLAR GARDEN

The Chinese Garden is a recent – and fabulous – addition to Dunedin. It is one of only 3 Ming Dynasty scholars’ gardens outside China. A scholar’s garden is the creation of a “spiritual utopia”, a contemplative space, an escape from daily concerns where one can re-connect with nature, the ancient way of life, one’s true self. The gardens try to capture the look of traditional Chinese paintings and the imagery created in poetry. To create this authentic garden, its wooden houses and structures were made in Shanghai using 4th century BC techniques – no nails, just mortise and tenon joints. The granite plinths and facings were hand chipped, the columns free-standing and not pinned.

The Chinese Garden is a recent – and fabulous – addition to Dunedin. It is one of only 3 Ming Dynasty scholars’ gardens outside China. A scholar’s garden is the creation of a “spiritual utopia”, a contemplative space, an escape from daily concerns where one can re-connect with nature, the ancient way of life, one’s true self. The gardens try to capture the look of traditional Chinese paintings and the imagery created in poetry. To create this authentic garden, its wooden houses and structures were made in Shanghai using 4th century BC techniques – no nails, just mortise and tenon joints. The granite plinths and facings were hand chipped, the columns free-standing and not pinned.  The buildings needed 380,000 terracotta roof tiles, handmade in Suzhou, China. After being assembled in Shanghai, the buildings were taken apart and shipped to Dunedin, along with 970 tons of rock and 130 tons of granite. Forty Chinese artisans from Shanghai did the installation in Dunedin.

The buildings needed 380,000 terracotta roof tiles, handmade in Suzhou, China. After being assembled in Shanghai, the buildings were taken apart and shipped to Dunedin, along with 970 tons of rock and 130 tons of granite. Forty Chinese artisans from Shanghai did the installation in Dunedin.

The Chinese word for “landscape” literally  means “mountains and waters”, and the mountain built here is from prized Lake Tai rock (from near Suzhou), a rock that represents wisdom and immortality; during the Song dynasty this sculpted rock was the most expensive object in the empire.

means “mountains and waters”, and the mountain built here is from prized Lake Tai rock (from near Suzhou), a rock that represents wisdom and immortality; during the Song dynasty this sculpted rock was the most expensive object in the empire.

We felt this Scholar’s Garden was indeed a wonderful, soothing, contemplative, fabulous place. By intent, there are visual surprises around every turn and corner (of which there are many!). Beckoning niches, contrasting colors and textures, or repeating patterns are traps for your eye and give you pause. Every window has a different intricate and marvelous grating. Let us take you on a tour. I’m just going to put a bunch of pictures below, as we walked around.

THE OTAGO MUSEUM – POLYNESIA and MELANESIA

This is a small but interesting museum that covers a number of subjects, but we were mostly  caught by the Polynesia/Melanesia wing – we really didn’t know much about the island regions of our world, and since we’re living in one of them, NZ, with Maori inhabitants, we thought we’d take a closer look. For orientation, here’s a map. As you can see, Polynesia is ‘way out there, specks floating in a big ocean!

caught by the Polynesia/Melanesia wing – we really didn’t know much about the island regions of our world, and since we’re living in one of them, NZ, with Maori inhabitants, we thought we’d take a closer look. For orientation, here’s a map. As you can see, Polynesia is ‘way out there, specks floating in a big ocean!

Before starting the Polynesia section, we took a quick look at some very nice Maori carvings that the museum had. They were made for a meeting house near Napier (North Island), and were carved in the 1870’s. We’re impressed!

For us, there are two very fascinating aspects of Polynesia. One is that the islands were settled one-by-one by seafarers using basically a canoe with a sail; these islands are anything but close, so the utter audacity of sailing off into the unknown is amazing. A sail and a prayer – if not a death wish – for a family or couple! I can see it now – “Hey sweetie, how about we sail off into that sunset and get away from here? We’ll find an island just for us. I mean, how big can the Pacific ocean be? You bring the water, I’ll paddle.” Yeah, not sure that pick-up line would work with Ginger.

The other fascinating aspect is the subsequent developmental changes (or their lack!) that occurred from a common culture. The islands were far enough apart that there was no chance for communication early on and, like Darwin’s finches, the cultures evolved in isolation. Alas, the museum does not directly address this topic, but it’s visible in the displays.

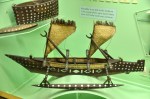

Let’s start with migration. Polynesian culture goes back 3 or 4 thousand years in some areas, originating from Southeast Asia and Taiwan. The far-flung areas we now call Polynesia were occupied by the late 1200’s AD. The picture to the left shows typical boats from different regions, and mostly they are riffs on the same theme, with a couple of exceptions that I’ll show first. China is the biggest exception – really not a Polynesian

Let’s start with migration. Polynesian culture goes back 3 or 4 thousand years in some areas, originating from Southeast Asia and Taiwan. The far-flung areas we now call Polynesia were occupied by the late 1200’s AD. The picture to the left shows typical boats from different regions, and mostly they are riffs on the same theme, with a couple of exceptions that I’ll show first. China is the biggest exception – really not a Polynesian  player, but interesting nonetheless. A very different boat! China had a permanent navy in the 1100’s during the Song Dynasty, with 52,000 marines! They were the leading maritime power in the early 1400’s, until subsequent emperors lost interest, eliminated their navy, and turned inward. Their boats had a different purpose (not island hopping/fishing) and thus had nothing in common with Polynesian boats. The other exception in this display is a

player, but interesting nonetheless. A very different boat! China had a permanent navy in the 1100’s during the Song Dynasty, with 52,000 marines! They were the leading maritime power in the early 1400’s, until subsequent emperors lost interest, eliminated their navy, and turned inward. Their boats had a different purpose (not island hopping/fishing) and thus had nothing in common with Polynesian boats. The other exception in this display is a  Kon-Tiki-like boat/raft from Peru, but there is little evidence that South America contributed much to Polynesia (except possibly to Easter Island). You may notice from the overall display at the start of this paragraph and in the pictures below that the New Zealand boat is different from most of its cohorts, having no sail and no outrigger. Its evolution is likely due to the shore-hugging short-distance travel around these large two islands, though sails and outriggers would have been used for the initial ocean crossings. You can also see that the war canoes of the Solomon Islands were very similar to that of the Maori, including the dramatically upraised prow. The other boats all have outriggers or a double hull, many have sails, and all are structurally similar.

Kon-Tiki-like boat/raft from Peru, but there is little evidence that South America contributed much to Polynesia (except possibly to Easter Island). You may notice from the overall display at the start of this paragraph and in the pictures below that the New Zealand boat is different from most of its cohorts, having no sail and no outrigger. Its evolution is likely due to the shore-hugging short-distance travel around these large two islands, though sails and outriggers would have been used for the initial ocean crossings. You can also see that the war canoes of the Solomon Islands were very similar to that of the Maori, including the dramatically upraised prow. The other boats all have outriggers or a double hull, many have sails, and all are structurally similar.

We thought the NZ Maori tattooing was extensive! This painful process was primarily done on Maori males, the females usually just doing their chins. For the Maori, tattooing was a mark of puberty as well as conveying information on a person’s lineage, tribe, occupation, rank, and exploits. Well, as you can see in this display, tattooing is obviously a Polynesian thing! And the Maori were conservative! Look at the Easter Island women, or the Samoa or Marquesas extensive tattoos (Ouch)! In these other cultures tattooing was also a mark of puberty, courage, rank and status.

We thought the NZ Maori tattooing was extensive! This painful process was primarily done on Maori males, the females usually just doing their chins. For the Maori, tattooing was a mark of puberty as well as conveying information on a person’s lineage, tribe, occupation, rank, and exploits. Well, as you can see in this display, tattooing is obviously a Polynesian thing! And the Maori were conservative! Look at the Easter Island women, or the Samoa or Marquesas extensive tattoos (Ouch)! In these other cultures tattooing was also a mark of puberty, courage, rank and status.

Decorative art such as combs and pendants, shown below, also show similarities across the island cultures, perhaps due to the similarity of available raw materials. The particular designs used in ornamentation, who wore them and how they were worn, however, varied from island to island. For instance, the pendants in the case below were decorated clam shells; it’s the same resource, but different cultures wore them on the chest, on the neck, or on the head.

Apparently house construction varied regionally across the islands, but there wasn’t much on display. I have two for you below, one a picture (New Caledonia), one a display (Samoa). Samoans were the “Architects of the Pacific”. Their houses were built without nails, screws or pegs. The open sides of the house allowed free circulation of air, but blinds of woven palm leaves could be lowered. Floors were of stone.

Tools had a lot of similarity. When a particular need would be the same – say, splitting breadfruit – the solution on different islands was usually quite similar, as shown with these breadfruit splitters to the left from Marquesas and Tahiti.

Often differences in tools among the islands were directly related to the availability of raw materials, such as the adzes below in coral, stone and jade.

Not everything is easily compared between islands. We’ll just show some bowls and interesting tools.

Music and celebrations are universal, as are drums and pipes.

And where there is dance, there are masks.

Finally, of course there is war. Islands are not an escape; the Maori were a warrior culture, as we have seen in earlier posts. When it came to war, the Polynesian islands diverged considerably, depending on the political culture. Some islands became fully developed kingdoms with little warfare, others divided into constantly warring tribes, such as NZ’s Maori. The primary force driving the culture one way or the other, in addition to population pressure, was geography. On level islands, where communication was essentially unimpeded, warfare was not chosen. On mountainous islands, with distinct boundaries like mountain ridges, warring groups were the norm. How interesting is that! Below are instruments of warfare, starting with the clubs.

In addition to clubs, there were spears and shields.

As a last picture, this is a Kiribati warrior from Tuvalu, an atoll. Atolls, just a few feet above the sea, support very little life other than a few trees and coconut palms (water was obtained from holes dug in the coral). With so few resources, humans struggled. However, here is a well-dressed warrior, on an atoll where we have been told warfare is not likely to occur! We don’t understand the need for armor, but the armor is in itself interesting; the cloth is coconut fiber decorated with shells. The helmet and stomach guard are of fish skin. Sharks teeth are used in the weapons. Quite a use of what you’ve got!

As a last picture, this is a Kiribati warrior from Tuvalu, an atoll. Atolls, just a few feet above the sea, support very little life other than a few trees and coconut palms (water was obtained from holes dug in the coral). With so few resources, humans struggled. However, here is a well-dressed warrior, on an atoll where we have been told warfare is not likely to occur! We don’t understand the need for armor, but the armor is in itself interesting; the cloth is coconut fiber decorated with shells. The helmet and stomach guard are of fish skin. Sharks teeth are used in the weapons. Quite a use of what you’ve got!

Well, I hope you enjoyed that long discourse on Polynesia and its insight into cultural evolution. My take-away is that if the resources are pretty much the same, the evolution is pretty much the same. If everyone lives on a flat area with few natural defenses, people make peace (conversely, it there are defensible borders, it becomes us-vs-them). I also thought it was interesting to get an insight into stone-age cultures existing into the late 1800’s!

Next post – Christchurch!

[…] Montaña miniatura de rocas apiladas en un jardín chino. Foto de trekinti.me […]