Cathedral Model, 1300’s – 1500’s

In 1072, William the Conqueror ordered that a Cathedral be built at Lincoln. Construction of the first Lincoln Cathedral was completed in 1092; it was rebuilt and expanded after a fire destroyed its timber roofing (1141). Destroyed again by an earthquake (1185), it was rebuilt on a magnificent scale beginning in 1192 using local rock; only the lower part of the Cathedral’s front and its two attached towers survive from the original Norman structure. The choir, eastern transepts and central nave were built in Early English Gothic style, but the rest followed architectural advances of pointed arches, flying buttresses and ribbed vaulting. Its crossing tower, completed in 1311, was an amazing engineering feat for the time. With a spire giving it a height of 525 ft, Lincoln Cathedral became the tallest building in the world, and the first to surpass the pyramid of Cheops in Egypt which had held that title for 4000 years. That honor, however, was lost after 238 years when the heavy, lead-coated but rotting wooden spire collapsed in a storm (1549). The spire was not replaced, a symbol of Lincoln’s economic and political decline at the time (see previous post, “The City of Lincoln”). Still, the cathedral is the third largest in Britain (in floor space) after St Paul’s (London) and York Minster (post of Jan 22, 2015; The York Minster).

Sitting on top of a hill, Lincoln Cathedral is visible for miles around and absolutely

dominates the city in an awe-inspiring, gorgeous way, irresistibly drawing your eyes. It’s a high point of medieval architecture, and also a navigation beacon; where are you in the city? Look for the Cathedral.

Let’s take a walk around the Cathedral. The overall plan is shown below; we’ll start with  the west-facing entrance. The previous Norman churches were short and thick-walled, with small windows resulting in dark interiors. The Gothic style made churches bright and spacious, but during the building of the Lincoln Cathedral the architects were writing the rule book, and it was literally trial and error (you’ll see some of this in the interior). As shown in the picture to the left, the

the west-facing entrance. The previous Norman churches were short and thick-walled, with small windows resulting in dark interiors. The Gothic style made churches bright and spacious, but during the building of the Lincoln Cathedral the architects were writing the rule book, and it was literally trial and error (you’ll see some of this in the interior). As shown in the picture to the left, the  Exchequer Gate that was the main entrance to the Cathedral close (arrow) does a great job of blocking the view of the stunning front of the Cathedral – particularly the preserved Norman (lower) structure. Further, as you can infer from the picture, once inside the gate you’re too close to get a good overview. Ah well, here’s the best I can do for the Cathedral entrance.

Exchequer Gate that was the main entrance to the Cathedral close (arrow) does a great job of blocking the view of the stunning front of the Cathedral – particularly the preserved Norman (lower) structure. Further, as you can infer from the picture, once inside the gate you’re too close to get a good overview. Ah well, here’s the best I can do for the Cathedral entrance.

Let me show you that entrance in detail, top to bottom, Gothic to Norman.

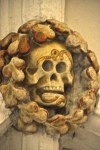

Again, the lower part is from the early 1100’s, now set within the harmonious upper region from the early 1200’s. The art that decorates the front entrance is impressive, from the Gothic repeating arch motifs in the first picture below to the many Norman carvings, two of which are shown below. The next-to-last picture shows the faithful being rescued from the mouth of hell (far right), the detail in the last picture showing that hell is not a nice

place. At the corners of this west-facing entrance are small towers that frame the front screen while continuing the arch motif – shown in the first 2 pictures below from the south side of the Cathedral. And we can’t leave the entrance view of the Cathedral without showing the commanding towers that flank the nave just behind the entrance.

The south transept also has an entrance to the Cathedral, shown below. In that last

picture, look at the base of the central column between the doors – it’s being hugged by

little devils, shown above.

The south side of the Cathedral is also highly decorated, with some interesting statues, many of them restored (Cathedral restoration costs $1.3 million/yr).

Then we come to the beautiful east side, and the chapter house.

The north side is more of the same, first picture below. It’s a stunningly beautiful

Cathedral, and inside it’s impressive as well. The first picture below is from near the entrance showing the many stained glass windows; the next pictures are from the nave looking inward and then looking back to the entrance. In that last picture, the blue overtones highlight the preponderance of blue in the stained glass!

Notice in the pictures below how the vaulting changes going down the side aisles. The vaulting was experimental during the building; it varies between the nave, aisles, choir and chapels, particularly in how the vaulting interacts with (ignores or enhances) the

Cathedral’s bays. The transept crossing that separated public access from the choir and alter is pretty spectacular. In addition to the tranquility of repeating designs, as

shown in the first picture below, there are interesting (and playful) carvings everywhere.

The choir dates from 1360-80 and is amazing, with beautifully carved wood stalls and bench-ends. I wasn’t happy with my capture of the choir, so I cribbed that last picture from the internet. It shows the “pulpitum”, the wood choir screen that separates the choir

from the nave; it dates from even earlier, the 1330’s. In addition to the intricately carved bench ends such as the one in the first picture below, the choir has 62 fascinating misericords or “mercy seats”. In the early medieval church, prayers were said standing,

Detail of the misericord carving, a lion fighting a dragon

and seats were constructed so they could be turned up. However, the seat underside could have a small shelf (the misericord), shown in the right picture above, which allowed the user to slightly reduce discomfort by leaning against it. The seats and carvings are in oak, all different, and delightful. Most of the seats were unfortunately in the down position (and the lighting was poor), so I bought their book and took some pictures of misericords from it, and I’ll share a bunch with you – they’re just that cool. I was told that the folding parts of the seats were installed as single blocks of oak, and each misericord was carved in place. No mistakes allowed! I didn’t believe that story at the time, but when I looked closely at the carvings, I could see that the wood grain in the seat and the carving line up! You can also see that in some of the figures below.

If you look back at the pictures of the choir shown earlier, the upper-right picture looks into the beautiful east end of the cathedral, completed in 1280. Other views are below.

The central region behind the main choir is called the Angel’s Choir because the upper arches are framed by stone carvings of angels playing medieval musical instruments. I’ve shown some of them below. That first picture is an angel playing a guitar precursor

called a citole. A famous stone carving in the Angel’s Choir is the Lincoln Imp. According to legend, two mischievous imps were sent by Satan to do evil work; after causing mayhem elsewhere in England, the imps came to Lincoln Cathedral where they smashed furniture and tripped up the Bishop. An angel appeared in the Angel Choir and ordered the imps to stop. One imp sat on a stone pillar and threw rocks at the angel, whereupon the angel turned him to stone; there he now sits.

called a citole. A famous stone carving in the Angel’s Choir is the Lincoln Imp. According to legend, two mischievous imps were sent by Satan to do evil work; after causing mayhem elsewhere in England, the imps came to Lincoln Cathedral where they smashed furniture and tripped up the Bishop. An angel appeared in the Angel Choir and ordered the imps to stop. One imp sat on a stone pillar and threw rocks at the angel, whereupon the angel turned him to stone; there he now sits.

Before I show you the cloister, let me backtrack to the transept crossing to look up at the Cathedral’s massive central tower from underneath. It’s gorgeous, but because I didn’t quite capture what I wanted to show, I’m including a

picture from the internet. Isn’t the geometry beautiful?

Now to the cloister. Access is via this impressive windowed corridor that duplicates the cloister design. The cloister itself (shown below) has a recent history – it was used for filming The Da Vinci Code, standing in for Westminster Abbey (which refused to permit filming).

Now to the cloister. Access is via this impressive windowed corridor that duplicates the cloister design. The cloister itself (shown below) has a recent history – it was used for filming The Da Vinci Code, standing in for Westminster Abbey (which refused to permit filming).

What is impressive is the view of the cloister against the magnificent Cathedral (and its “Dean’s Eye” north transept window), shown below. And there is an added bonus; part of the floor in a corner of the cloister is a mosaic from the Roman fort that occupied this hill!

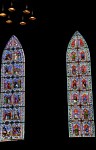

At last, now the stained glass windows! There are a lot of them, including some fabulous medieval glass. We’ll start with the west entrance, pictures below. Beautiful, yes?

There are many, many windows in the nave. Like most churches, the stained glass is mostly from the mid 1800’s, following a rebirth in its popularity. There’s too much to show, so I’ll just do a little (which will still be a lot). Although the windows do not present the life of Jesus sequentially, it seems that all the stories of the New Testament are here, examples shown below. The windows are gorgeous, aren’t they?

There are many, many windows in the nave. Like most churches, the stained glass is mostly from the mid 1800’s, following a rebirth in its popularity. There’s too much to show, so I’ll just do a little (which will still be a lot). Although the windows do not present the life of Jesus sequentially, it seems that all the stories of the New Testament are here, examples shown below. The windows are gorgeous, aren’t they?

You didn’t think we were done with the nave windows, did you? There’s also the Old Testament, and monk history, and ….

Now let me show you the gorgeous east end windows. The first picture below shows most of that east wall, overwhelmingly in blue. The next three pictures show the left and right side windows in normal light; then I’ve shown the right side window at night, lit by the outside lights of the cathedral. The windows are beautiful in any light!

The large, central – and very blue! – window is simply spectacular, commanding attention. It is one of England’s largest windows.

At last, the good stuff! Although stained glass reached its height as an art form in the Middle Ages, there isn’t that much of it left; huge numbers of windows were destroyed in the French Revolution and Protestant Revolution (for instance, the English Parliament ordered all images of the Virgin Mary and the Trinity removed from churches; Protestant mobs were less selective). Until its revival in the mid 1800’s (600 years later), stained glass was a lost art. Colored glass became scarce, necessitating the painting of white glass. The little decorative glass that was produced was mostly small heraldic panels for city halls. Lincoln Cathedral has some examples of stained glass from this time in one of its side rooms, shown below.

The medieval stained glass in the Lincoln Cathedral resides mostly at the ends of the transepts. Each transept has a rose window, an uncommon feature in English medieval architecture. The north transept has the “Dean’s Eye”, shown below, which depicts the Last Judgement. It’s part of the original structure of the Cathedral, finished in 1220.

Underneath the rose window are a set of 5 windows with gorgeous geometrical designs,

and below them these final two windows.

The south transept has the “Bishop’s Eye”; it too was built in 1220, but rebuilt around 1330. It’s one of the largest examples of curvilinear tracery in medieval architecture, and was a challenge for the designers (and glass artists). The window from outside the Cathedral and from inside the transept is shown below.

Most cathedral windows during this time displayed biblical images; that’s hard to do with such curvilinear shapes, so the window is instead a mosaic of color. I was told that within the window there are images of the saints Paul, Andrew, and James; if so, it requires imagination! The Bishop’s Eye is shown in more detail below.

Details from two of the lower windows are shown below.

Goodness! Could there be more to show of this majestic cathedral? Of course! But we never caught the chapter house when it was open. There’s also lots of treasure, but I’ll only show two pictures.

Enough is enough! I will simply end with a view of the  Cathedral at night. It is stunningly beautiful.

Cathedral at night. It is stunningly beautiful.

You masochists that have waded the whole way through this long, long post, I salute you!

The next (shorter! Promise!) post will finish the fair city of Lincoln, and will include the Lincoln Castle, the Magna Carta, and the Bishop’s Palace.

castle design. Built on flat marshy ground with no natural defenses, the castle incorporates concentric rings of fortifications – a double ring of walls surrounded by a moat. The innermost wall is higher than the outer, providing greatly increased firepower. A fortified dock was built to give sea access, allowing the castle to withstand sieges (as shown in the picture, the sea is more distant now). However, problems in Scotland shifted the king’s priorities, and the castle was never finished. An artist’s concept

castle design. Built on flat marshy ground with no natural defenses, the castle incorporates concentric rings of fortifications – a double ring of walls surrounded by a moat. The innermost wall is higher than the outer, providing greatly increased firepower. A fortified dock was built to give sea access, allowing the castle to withstand sieges (as shown in the picture, the sea is more distant now). However, problems in Scotland shifted the king’s priorities, and the castle was never finished. An artist’s concept  of what the castle would have looked like, had it been finished, is shown to the left. The picture shows a much more imposing structure that would have been twice the height of the squat one we see today. The inner walls look particularly impenetrable. The south gate seen at the lower right faced the sea and was the main castle entrance as well as the dock. A magnification of this artist’s rendition is shown below, along with a picture of the way it looks now. The red arrows point to the dock’s

of what the castle would have looked like, had it been finished, is shown to the left. The picture shows a much more imposing structure that would have been twice the height of the squat one we see today. The inner walls look particularly impenetrable. The south gate seen at the lower right faced the sea and was the main castle entrance as well as the dock. A magnification of this artist’s rendition is shown below, along with a picture of the way it looks now. The red arrows point to the dock’s shown here. Beneath the Gunner’s Walk was a corn mill for self-sufficiency, the mill turned by differences in water level between the moat and the sea. Whereas the water in the dock was supplied by the sea, the water in the moat was supplied by a freshwater stream; the level between the two was regulated by a sluice gate in the Gunner’s Walk. How clever! The town wall started from here, but wasn’t finished until 1414.

shown here. Beneath the Gunner’s Walk was a corn mill for self-sufficiency, the mill turned by differences in water level between the moat and the sea. Whereas the water in the dock was supplied by the sea, the water in the moat was supplied by a freshwater stream; the level between the two was regulated by a sluice gate in the Gunner’s Walk. How clever! The town wall started from here, but wasn’t finished until 1414.

A schematic of Caernarfon Castle is shown here. As you can see, it’s all walls and towers; construction was stopped in 1330 before it was completed. Although there were once interior buildings, none have survived.

A schematic of Caernarfon Castle is shown here. As you can see, it’s all walls and towers; construction was stopped in 1330 before it was completed. Although there were once interior buildings, none have survived.

Arrow loops are everywhere in the walls, creating a veritable medieval machine gun. These arrow loops were high-tech for their time: not only were they angled to allow each archer to cover a wide area, they also had an angled central pillar in the center of each loop to provide extra protection.

Arrow loops are everywhere in the walls, creating a veritable medieval machine gun. These arrow loops were high-tech for their time: not only were they angled to allow each archer to cover a wide area, they also had an angled central pillar in the center of each loop to provide extra protection.

Returning to the Caernarfon Castle overview, re-shown here, the jutting structure behind the kitchen site is the unfinished rear of the King’s Gate, and across from that the Chamberlain Tower, with the North-East Tower, Watch Tower and Queen’s Gate in the background. The pictures below look in the opposite direction toward the huge three-

Returning to the Caernarfon Castle overview, re-shown here, the jutting structure behind the kitchen site is the unfinished rear of the King’s Gate, and across from that the Chamberlain Tower, with the North-East Tower, Watch Tower and Queen’s Gate in the background. The pictures below look in the opposite direction toward the huge three-

picture of the Granary and North-East Towers, that there are notched walls ready for an expansion that never came.

picture of the Granary and North-East Towers, that there are notched walls ready for an expansion that never came.

a good overview of the castle. Notice that it’s divided into two sections, a front and a back. The front was the working part of the castle; the back had the royal apartments. The castle was at the cutting edge of military technology, with thick walls, rounded towers and turrets providing lethal fields of fire, a solid rock base, and royal apartments that could be defended separately. Well supplied with fresh water from a spring-fed well, 91 feet down, and with its own dock, it could withstand sieges indefinitely. Nothing on this scale had been seen before in Wales, which at that time had no real cities. The last picture above and the picture to the left show how intimidating it still is.

a good overview of the castle. Notice that it’s divided into two sections, a front and a back. The front was the working part of the castle; the back had the royal apartments. The castle was at the cutting edge of military technology, with thick walls, rounded towers and turrets providing lethal fields of fire, a solid rock base, and royal apartments that could be defended separately. Well supplied with fresh water from a spring-fed well, 91 feet down, and with its own dock, it could withstand sieges indefinitely. Nothing on this scale had been seen before in Wales, which at that time had no real cities. The last picture above and the picture to the left show how intimidating it still is.

and the Great Hall dining area, shown in the lower right picture. A representation of how the chapel and dining hall looked in the 1280’s is shown here on the left. People ate here regardless of rank; status was indicated by distance from the top table (and the further away, the plainer the food).

and the Great Hall dining area, shown in the lower right picture. A representation of how the chapel and dining hall looked in the 1280’s is shown here on the left. People ate here regardless of rank; status was indicated by distance from the top table (and the further away, the plainer the food).

Not all went well on this trip to Conwy; descending a castle stairwell, perhaps foolishly in sandals, I slipped on a wet step and fell backward. I protected my camera, but alas, not my hand, as shown in the x-ray. I apparently sat on the hand, and the buns of steel did the rest; two fingers with spiral fractures. Broken fingers are bad enough, but worse, that’s the end of the plan to climb Mt. Snowdon. What a disaster! So back we go to poor Britt in Lincoln.

Not all went well on this trip to Conwy; descending a castle stairwell, perhaps foolishly in sandals, I slipped on a wet step and fell backward. I protected my camera, but alas, not my hand, as shown in the x-ray. I apparently sat on the hand, and the buns of steel did the rest; two fingers with spiral fractures. Broken fingers are bad enough, but worse, that’s the end of the plan to climb Mt. Snowdon. What a disaster! So back we go to poor Britt in Lincoln. You may remember from our first Lincoln post (The City of Lincoln) that in 1068 William The Conquerer built Lincoln Castle as a very visible symbol of power at the top of Steep Hill. This picture, taken from the Lincoln Cathedral, shows the Cathedral’s Exchequer Gate in the foreground, and in the background, the walls of Lincoln Castle. It may be a small town, but it is not a small castle!

You may remember from our first Lincoln post (The City of Lincoln) that in 1068 William The Conquerer built Lincoln Castle as a very visible symbol of power at the top of Steep Hill. This picture, taken from the Lincoln Cathedral, shows the Cathedral’s Exchequer Gate in the foreground, and in the background, the walls of Lincoln Castle. It may be a small town, but it is not a small castle!

This model of the castle shows how roomy it is inside the walls. The barbican entrance shown above is on the right side of the model. The castle has been re-purposed over the centuries, and nothing on the inside, other than the walls and towers themselves, looks anywhere close to its 1068 roots. Below is the view of the courtyard from the castle wall above the main entrance. That building straight ahead is the Courthouse, built in 1826. Lincoln Castle was always a seat of justice,

This model of the castle shows how roomy it is inside the walls. The barbican entrance shown above is on the right side of the model. The castle has been re-purposed over the centuries, and nothing on the inside, other than the walls and towers themselves, looks anywhere close to its 1068 roots. Below is the view of the courtyard from the castle wall above the main entrance. That building straight ahead is the Courthouse, built in 1826. Lincoln Castle was always a seat of justice,

the west-facing entrance. The previous Norman churches were short and thick-walled, with small windows resulting in dark interiors. The Gothic style made churches bright and spacious, but during the building of the Lincoln Cathedral the architects were writing the rule book, and it was literally trial and error (you’ll see some of this in the interior). As shown in the picture to the left, the

the west-facing entrance. The previous Norman churches were short and thick-walled, with small windows resulting in dark interiors. The Gothic style made churches bright and spacious, but during the building of the Lincoln Cathedral the architects were writing the rule book, and it was literally trial and error (you’ll see some of this in the interior). As shown in the picture to the left, the  Exchequer Gate that was the main entrance to the Cathedral close (arrow) does a great job of blocking the view of the stunning front of the Cathedral – particularly the preserved Norman (lower) structure. Further, as you can infer from the picture, once inside the gate you’re too close to get a good overview. Ah well, here’s the best I can do for the Cathedral entrance.

Exchequer Gate that was the main entrance to the Cathedral close (arrow) does a great job of blocking the view of the stunning front of the Cathedral – particularly the preserved Norman (lower) structure. Further, as you can infer from the picture, once inside the gate you’re too close to get a good overview. Ah well, here’s the best I can do for the Cathedral entrance.

called a citole. A famous stone carving in the Angel’s Choir is the Lincoln Imp. According to legend, two mischievous imps were sent by Satan to do evil work; after causing mayhem elsewhere in England, the imps came to Lincoln Cathedral where they smashed furniture and tripped up the Bishop. An angel appeared in the Angel Choir and ordered the imps to stop. One imp sat on a stone pillar and threw rocks at the angel, whereupon the angel turned him to stone; there he now sits.

called a citole. A famous stone carving in the Angel’s Choir is the Lincoln Imp. According to legend, two mischievous imps were sent by Satan to do evil work; after causing mayhem elsewhere in England, the imps came to Lincoln Cathedral where they smashed furniture and tripped up the Bishop. An angel appeared in the Angel Choir and ordered the imps to stop. One imp sat on a stone pillar and threw rocks at the angel, whereupon the angel turned him to stone; there he now sits.

Now to the cloister. Access is via this impressive windowed corridor that duplicates the cloister design. The cloister itself (shown below) has a recent history – it was used for filming The Da Vinci Code, standing in for Westminster Abbey (which refused to permit filming).

Now to the cloister. Access is via this impressive windowed corridor that duplicates the cloister design. The cloister itself (shown below) has a recent history – it was used for filming The Da Vinci Code, standing in for Westminster Abbey (which refused to permit filming).

There are many, many windows in the nave. Like most churches, the stained glass is mostly from the mid 1800’s, following a rebirth in its popularity. There’s too much to show, so I’ll just do a little (which will still be a lot). Although the windows do not present the life of Jesus sequentially, it seems that all the stories of the New Testament are here, examples shown below. The windows are gorgeous, aren’t they?

There are many, many windows in the nave. Like most churches, the stained glass is mostly from the mid 1800’s, following a rebirth in its popularity. There’s too much to show, so I’ll just do a little (which will still be a lot). Although the windows do not present the life of Jesus sequentially, it seems that all the stories of the New Testament are here, examples shown below. The windows are gorgeous, aren’t they?

Cathedral at night. It is stunningly beautiful.

Cathedral at night. It is stunningly beautiful. More pertinent to us, however, is that it is home to younger son Britt and family, and we can visit! And visit. And visit. Little did poor Britt know that we would be there for an extended time. After Ginger and I left to visit Barcelona (Spain), I separated my shoulder trying to tackle a would-be camera thief on marble stairs (a topic for a future Barcelona post), so back to Lincoln we went to recover. There I fell and broke (badly) 2 ribs, and as I was recovering, Ginger needed major abdominal surgery. So we basically moved into Britt’s house for quite a while. Newly recovered and off to Wales, I slipped in a castle stairwell and broke two fingers (badly; spiral fractures); so back to Britt’s we went. Soooooo – let me show you some of Lincoln! It’s actually a very interesting town.

More pertinent to us, however, is that it is home to younger son Britt and family, and we can visit! And visit. And visit. Little did poor Britt know that we would be there for an extended time. After Ginger and I left to visit Barcelona (Spain), I separated my shoulder trying to tackle a would-be camera thief on marble stairs (a topic for a future Barcelona post), so back to Lincoln we went to recover. There I fell and broke (badly) 2 ribs, and as I was recovering, Ginger needed major abdominal surgery. So we basically moved into Britt’s house for quite a while. Newly recovered and off to Wales, I slipped in a castle stairwell and broke two fingers (badly; spiral fractures); so back to Britt’s we went. Soooooo – let me show you some of Lincoln! It’s actually a very interesting town.

this pristine area juxtaposes a lush green countryside with treeless hills reminiscent of the Scottish highlands – quite a fascinating mix! However, getting that lush green comes at a cost; rain, mixed with occasional “bright spots”. Alas, the pictures below should show brilliant colors (it was fall when we were there), but “gloom” and “brilliant” don’t coexist easily. Still, there were occasional bright spots like that shown above – which, by the way, was absolutely spectacular, in spite of the gloom!

this pristine area juxtaposes a lush green countryside with treeless hills reminiscent of the Scottish highlands – quite a fascinating mix! However, getting that lush green comes at a cost; rain, mixed with occasional “bright spots”. Alas, the pictures below should show brilliant colors (it was fall when we were there), but “gloom” and “brilliant” don’t coexist easily. Still, there were occasional bright spots like that shown above – which, by the way, was absolutely spectacular, in spite of the gloom! the earliest stone circles in Britain and possibly in Europe. From that aerial picture, it contains an unusual rectangular inclusion, called the “sanctuary”. You may recall our previous encounters with similar stone circles in Scotland and Ireland (

the earliest stone circles in Britain and possibly in Europe. From that aerial picture, it contains an unusual rectangular inclusion, called the “sanctuary”. You may recall our previous encounters with similar stone circles in Scotland and Ireland (

picture isn’t shining on us. Today we’re driving a loop that goes through a lot of Lake District scenery: Newlands Valley, Buttermere Village, the Honister Pass, Borrowdale, and Derwentwater Lake. We’re heading west, and our two-lane road quickly becomes a single lane, as shown in the first picture below (although the road does have turnouts). The subsequent pictures show picture-book idyllic scenery.

picture isn’t shining on us. Today we’re driving a loop that goes through a lot of Lake District scenery: Newlands Valley, Buttermere Village, the Honister Pass, Borrowdale, and Derwentwater Lake. We’re heading west, and our two-lane road quickly becomes a single lane, as shown in the first picture below (although the road does have turnouts). The subsequent pictures show picture-book idyllic scenery.

We’re now heading up to glacier-carved Honister Pass. This picture also looks back at our previous waterfall, far in the distance. The river adds a new element to this pretty area.

We’re now heading up to glacier-carved Honister Pass. This picture also looks back at our previous waterfall, far in the distance. The river adds a new element to this pretty area.

This house, the oldest in Glasgow, was built by (and near) the Glasgow Cathedral in 1471. It likely reflects “the lifestyles of the rich and famous” for that time. It was originally the home of one of the 32 canons who managed a part of the Cathedral’s vast diocese – in this case the land at Provan (the other 31 canons were similarly housed). By the 1600’s it had become a private home; by the 1700’s, and for the next 200 years, it was used as an inn, with rooms on the upper floors and a wide range of shops on the ground floor. A small extension housed the city’s hangman. It’s a pretty cool place, all stone with massive, rough-hewn, low-hanging beams and fireplaces everywhere. The entrance opens into the

This house, the oldest in Glasgow, was built by (and near) the Glasgow Cathedral in 1471. It likely reflects “the lifestyles of the rich and famous” for that time. It was originally the home of one of the 32 canons who managed a part of the Cathedral’s vast diocese – in this case the land at Provan (the other 31 canons were similarly housed). By the 1600’s it had become a private home; by the 1700’s, and for the next 200 years, it was used as an inn, with rooms on the upper floors and a wide range of shops on the ground floor. A small extension housed the city’s hangman. It’s a pretty cool place, all stone with massive, rough-hewn, low-hanging beams and fireplaces everywhere. The entrance opens into the

the unconquered north, in AD 142 Hadrian’s successor Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered a new wall built about 70 miles further north of the existing wall. Again these clever Romans somehow knew where the shortest distance would be, and the wall was built from the river Clyde just above present-day Glasgow to the Firth of Forth just west of present-day Edinburgh. The wall was 39 miles long, about 13 feet high, and 16 feet wide; it took 12 years to complete. It was built of turf and earth on a stone foundation. Like Hadrian’s Wall it had a deep ditch on the north side and a military road on the south. A wooden palisade is thought to have been on top. It was protected by 17 forts with about 10

the unconquered north, in AD 142 Hadrian’s successor Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered a new wall built about 70 miles further north of the existing wall. Again these clever Romans somehow knew where the shortest distance would be, and the wall was built from the river Clyde just above present-day Glasgow to the Firth of Forth just west of present-day Edinburgh. The wall was 39 miles long, about 13 feet high, and 16 feet wide; it took 12 years to complete. It was built of turf and earth on a stone foundation. Like Hadrian’s Wall it had a deep ditch on the north side and a military road on the south. A wooden palisade is thought to have been on top. It was protected by 17 forts with about 10 “fortlets”, very likely on (Roman) mile spacings. In spite of the effort it took to build the wall, it was abandoned only 8 years after completion (162 AD), the garrisons being relocated back to Hadrian’s Wall. Following a series of attacks in 197 AD, the emperor Septimius Severus arrived in Scotland in 208 to secure the frontier. He ordered repairs and re-established legions at Antonine’s Wall (after which the wall also became known as the Severan Wall). Only a few years later the wall was abandoned for the second time and never fortified again.

“fortlets”, very likely on (Roman) mile spacings. In spite of the effort it took to build the wall, it was abandoned only 8 years after completion (162 AD), the garrisons being relocated back to Hadrian’s Wall. Following a series of attacks in 197 AD, the emperor Septimius Severus arrived in Scotland in 208 to secure the frontier. He ordered repairs and re-established legions at Antonine’s Wall (after which the wall also became known as the Severan Wall). Only a few years later the wall was abandoned for the second time and never fortified again.

art (stained glass, tapestries), Egyptian, Islamic and Chinese art, French Impressionist paintings, sculpture, armor, architecture, furniture…. Be prepared for ecclectic! So where to start, eh? How about this vase, found in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, from 100-200 AD (restoration in the 1700’s). Fill it with wine and take a bath?

art (stained glass, tapestries), Egyptian, Islamic and Chinese art, French Impressionist paintings, sculpture, armor, architecture, furniture…. Be prepared for ecclectic! So where to start, eh? How about this vase, found in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, from 100-200 AD (restoration in the 1700’s). Fill it with wine and take a bath?

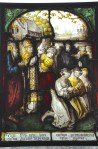

world. The 3 panels shown on the left came from a French cathedral from about 1280 (!), showing a wedding party in the center, with kitchen scenes above and below that referenced the trade guild that paid for the window. The only paint on the glass is a brown metal oxide that defines the faces, hair and folds of the clothes. The individual pieces of colored glass are small, and therefore the many lead canes holding them together made the panels strong. There are few restorations, and the window looks almost exactly like it did 750 years ago.

world. The 3 panels shown on the left came from a French cathedral from about 1280 (!), showing a wedding party in the center, with kitchen scenes above and below that referenced the trade guild that paid for the window. The only paint on the glass is a brown metal oxide that defines the faces, hair and folds of the clothes. The individual pieces of colored glass are small, and therefore the many lead canes holding them together made the panels strong. There are few restorations, and the window looks almost exactly like it did 750 years ago.

Our final look at a Mackintosh tea room is “The Willow TeaRooms and Gift Shop”. These rooms are not in a museum – they constitute a 1903 Mackintosh building that is still serving food and tea to the public. Below are pictures of these rooms as they looked in 1905;

Our final look at a Mackintosh tea room is “The Willow TeaRooms and Gift Shop”. These rooms are not in a museum – they constitute a 1903 Mackintosh building that is still serving food and tea to the public. Below are pictures of these rooms as they looked in 1905;