The “Isle of Harris” is a misnomer; it’s not really its own island. This largest of the Outer Hebrides Islands is actually called Lewis and Harris, one island, Harris being the southern part. But what the hey, let’s go with convention and call it the Isle of Harris. We’re going there in part for the scenery and in part because that’s where they weave the famous Harris Tweed – we’re hoping to buy some. Sports coats and hoodies, here we come!

We mentioned the Lewis part of the island previously – remember the Lewis Chessmen (post of Edinburgh I)?

Coming from the mountains of the Isle of Skye, we were unprepared for the Isle of Harris. It is so different! Below are pictures of the coastline as we approached the city of Harris.

The mountains are anything but craggy; they’re weathered, with a very speckled appearance. It does not look like good farm land! As we travel inland, it’s all the same; mostly rock, with a little bit of heather and grass thrown in for contrast.

Actually, at least in spots it’s not all solid rock underfoot. Some exposed areas show deep layers of peat.

Actually, at least in spots it’s not all solid rock underfoot. Some exposed areas show deep layers of peat.

This southern part of Harris has a number of gorgeous unspoiled beaches, one of them shown below. I think it’s pretty cool to see beach, sea and mountains all in the same view! The beach goes on forever, and we practically have it all to ourselves.

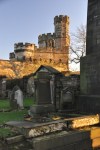

Also in southern Harris is the medieval church Tur Chliamain (St. Clements Church). The

church was built around 1520 by the MacLeod clan chiefs of Dunvegan and Harris as their future burial place. Like most things that old, it’s not exactly the original structure. The church fell into ruin after the Protestant Reformation of 1560; it was rebuilt 200 years later by a MacLeod, and restored again in 1873. Still, it’s believably old, and beautiful in its simplicity, as shown in the first two figures below.

The church contains a number of tombs of important MacLeod chiefs outfitted in their battle armor. The bottom left picture (above) shows the tomb of Alasdair MacLeod, 8th Chief of the MacLeods, who personally commissioned his tomb and its carvings and was buried here around 1545. The last picture above shows 4 stones with sword carvings dating from the 1400’s and 1500’s that once marked the burial places for members of Clan MacLeod. The swords represented strength and power.

In the pictures below you can see how picturesque this place can be, as well as to show that there are a few areas that aren’t covered by stones.

The northern part of Harris is more mountainous, as shown below.

The (very) small village of Arnol on the west coast of the Isle of Lewis used to be a thriving township with 40 crofts; now there are far fewer. Crofts were plots of land rented to tenant farmers in the early 1700’s; rents were high, tenant rights were non-existent, and most were barely making it. More than a century later their land was given to them via special legislation. Here on Lewis the houses on a croft are called blackhouses, and Arnol has a lot of them – but most are deserted ruins. One that has been preserved is now a state-owned Blackhouse Museum, shown below. Alas it’s closed, but it is still interesting! It’s huge! But the doors are small – even Ginger would have to stoop to enter.

There’s an interesting attached circular “beehive” structure in the back; maybe a kitchen? The next-to-last picture shows how small the beehive door is. That hole in the roof just above Ginger’s head must be some sort of exhaust, unusual in these structures. Finally, in the back there is a decent supply of drying peat logs. A historical sign says that the peat fire was the center of family life in a croft and was never allowed to go out. The smoke rising into and through the roof had benefits: it killed bugs, and when the roof was replaced, the smoke-ladened thatch made excellent fertilizer for the fields.

Nearby we spot another coo. Isn’t she cute??

Nearby we spot another coo. Isn’t she cute??

Further down the road we encounter the larger Gearrannan Blackhouse Village, consisting of 9 restored traditional thatched cottages. The good news is that they’re open! The bad news is that most of them are self-catered apartments for rent, not for sight-seeing. However, the oldest blackhouse is a museum, and a chance to learn

more. The low profile and insulating thatch of these houses were designed for the Hebrides weather, and for 300 years people eked out a living here; they paid their rent or were quickly evicted if they didn’t. When the crofters were given their land in 1886, their approach to the houses – now theirs! – changed. The blackhouses in this village date back only to those late 1800s (they seem much older). Of note, these particular cottages were continuously lived in until 1974, when the last few elderly residents decided they no longer wanted to put up with the annual maintenance of thatch and stonework.

In earlier years the blackhouse accommodated livestock as well as people. People lived at one end and the animals lived at the other with a partition between them (the livestock would also add to the warmth of the house). A model of such a blackhouse was in the museum and was pretty cool. The central room contained the kitchen.

On to something different! For those who do not know about the famous Harris tweed, here’s a little history. For centuries the islanders of the Outer Hebrides wove cloth by hand, and by the late 1700’s cloth production was a stable industry for crofters. With the industrial revolution, mainland manufacturers turned to mechanization, but not the Outer Hebrides, where the high-quality handmade fabric was ideal for protection from their cold, wet climate. Because the cloth was hard-wearing and water resistant, a Countess of a north Harris estate had clothes made in the family tartan for her staff. She was quick to see that the jackets would be ideal attire for the pursuit of country sports and the outdoor lifestyle that was prevalent among the landed gentry and aristocracy. With promotion, it soon became the fabric of choice for the wealthy, and the rest is history. Today, to be called Harris Tweed, the cloth must be made from pure virgin wool dyed and spun in the Outer Hebrides, hand woven on a treadle loom by the islanders at their homes in the Outer Hebrides, and finished in the Outer Hebrides. Every 50 yards of Harris Tweed are checked by an inspector from the Harris Tweed Authority before being stamped for approval. As we drive around Harris and Lewis, we spot a sign from a weaver welcoming guests. He’s in a small shed adjacent to his house. Heating is by peat fire. The encounter

was fascinating. The treadle loom looks its age, with gears and many moving parts working in the best Rube Goldberg fashion, spinning and turning and clattering away. The work seems slow and tedious; no wonder the weaver wanted company. Alas, the particular cloth he was weaving was a single (vibrant!) color, and not our taste.

Those familiar with Harris Tweed know that one of their distinguishing characteristics is the use of a complex blend of colors. What looks like a gray or brown jacket could easily have 20 or so colors in it, including deep red, purple, rusty orange, green, etc. Clothes from Harris Tweed are amazing. Take a look at that brown sport coat I bought.

On closer inspection, the cloth seems to have every color in it except brown! Isn’t that cool? We will be sooooo stylish in our dotage.

Our last topic is the amazing Callanish (Gaelic: Calanais) Stones on the west coast of Lewis. That aerial view to the left is a picture I took of a postcard. I would describe the site as a low ridge on which there is an arrangement of standing stones placed in a pattern of a cross, with the long arms oriented north-south, encompassing a central stone circle. Yeah, but that kinda misses the fact that they are 5000 years old and likely a focus for prehistoric religious activity for at least 1500 years (!). The ritual landscape was wider than this site; within a radius of 3 miles are 12 other standing-stone sites, a couple of them just visible from here. The stones were erected in the late Neolithic era, starting around

Our last topic is the amazing Callanish (Gaelic: Calanais) Stones on the west coast of Lewis. That aerial view to the left is a picture I took of a postcard. I would describe the site as a low ridge on which there is an arrangement of standing stones placed in a pattern of a cross, with the long arms oriented north-south, encompassing a central stone circle. Yeah, but that kinda misses the fact that they are 5000 years old and likely a focus for prehistoric religious activity for at least 1500 years (!). The ritual landscape was wider than this site; within a radius of 3 miles are 12 other standing-stone sites, a couple of them just visible from here. The stones were erected in the late Neolithic era, starting around

2900 BC (just for perspective, the earliest known Egyptian pyramids were started about 300 years later, around 2630 BC). Up close, these silent vigil stones are impressive in

their massive size, ethereal beauty and mysterious function. The purpose of the site is not known, although there are a number of folklore, religious and astronomical theories (petrified giants who would not convert to Christianity, a prehistoric lunar observatory …). Note in the next-to-last picture how big those suckers are compared to Ginger! That largest central monolith weighs about 7 tons (requiring a Herculean effort to transport, position and erect) and has an almost perfect north-south alignment. The chambered tomb, or what’s left of it as shown in the last picture, was built somewhat later than the stone circle and contained ceramic pots holding cremated bodies dating between 2000 and 1700 BC. Somewhere between 1500-1000 BC the complex fell out of use and was despoiled by later Bronze Age farmers.

Although the stones are stunning – almost haunting – it is not clear to me why our Neolithic people chose this particular site; the area is pretty, as shown below, but nothing

extraordinary. Of course this is 5000 years later ….. I have to think these remarkable monuments from our ancient European ancestors attest to their – and humankind’s – need to better understand the world and their place in it. We’re still asking those questions, aren’t we.

This is a last shot of the Isle of Harris. It is a pretty place. The next set of posts, and the last from bonny Scotland, will be from Glasgow with its fabulous Mackintoshes.

This is a last shot of the Isle of Harris. It is a pretty place. The next set of posts, and the last from bonny Scotland, will be from Glasgow with its fabulous Mackintoshes.

Sleat is mostly flat, but it has great views across the water to the mainland (picture on the left). The series of pictures below capture Sleat nicely. They were taken from a single location, although the first picture was taken on a different day than the rest.

Sleat is mostly flat, but it has great views across the water to the mainland (picture on the left). The series of pictures below capture Sleat nicely. They were taken from a single location, although the first picture was taken on a different day than the rest.

This morning I’m greeted by the Sgùrr nan Gillean peak looking quite spiffy. It would be fun to climb that beast, but not this trip; I kinda doubt it’s a day hike, plus there would be mutiny.

This morning I’m greeted by the Sgùrr nan Gillean peak looking quite spiffy. It would be fun to climb that beast, but not this trip; I kinda doubt it’s a day hike, plus there would be mutiny.

the first picture above is called “The Needle”. As you can see in the other two pictures, we’re following the cliff wall to new mini-mountains up ahead. The trail is easy enough but it’s narrow, and occasionally when the hillside is quite steep, the downhill edges of the trail become a bit unstable. The trail shown in the left picture is less than a foot wide; walking across it is not unlike walking a gymnast’s balance beam, with consequences for slipping off.

the first picture above is called “The Needle”. As you can see in the other two pictures, we’re following the cliff wall to new mini-mountains up ahead. The trail is easy enough but it’s narrow, and occasionally when the hillside is quite steep, the downhill edges of the trail become a bit unstable. The trail shown in the left picture is less than a foot wide; walking across it is not unlike walking a gymnast’s balance beam, with consequences for slipping off.

I love this picture! The view is fabulous, but it also helps you appreciate the huge “sloping plateau” I’m on, which is very much like one to the far right in this picture, but much bigger.

I love this picture! The view is fabulous, but it also helps you appreciate the huge “sloping plateau” I’m on, which is very much like one to the far right in this picture, but much bigger. I’ve finally reached the top; this high up, there’s a commanding view, shown on the left.

I’ve finally reached the top; this high up, there’s a commanding view, shown on the left.

to a rural setting, and after traveling back and forth on a narrow winding road devoid of signs or parking lots, we decide that two cars parked at the edge of the road must mark the spot, and off we hike up some hills. Behind us in the distance is a pretty impressive waterfall!

to a rural setting, and after traveling back and forth on a narrow winding road devoid of signs or parking lots, we decide that two cars parked at the edge of the road must mark the spot, and off we hike up some hills. Behind us in the distance is a pretty impressive waterfall! and scrub trees, we begin to see a unique landscape of furrowed conical hills. The glen itself is a small secluded area – fitting for small fairies, right? It has a rocky pinnacle that will provide an overview, so up I go. The scramble is a bit precarious, with edges on both sides, and Ginger decides to explore from below.

and scrub trees, we begin to see a unique landscape of furrowed conical hills. The glen itself is a small secluded area – fitting for small fairies, right? It has a rocky pinnacle that will provide an overview, so up I go. The scramble is a bit precarious, with edges on both sides, and Ginger decides to explore from below.

Now on to the Dunvegan Peninsula! The roads here – like many of those on Skye – are one lane, making driving more interesting. Usually the roads are paved, but not always. And as shown in this image, I think “traffic jam” on this island means nose to butt sheep on the road.

Now on to the Dunvegan Peninsula! The roads here – like many of those on Skye – are one lane, making driving more interesting. Usually the roads are paved, but not always. And as shown in this image, I think “traffic jam” on this island means nose to butt sheep on the road.

We’ve relocated further south to be near the Cuillin Hills, shown here off in the distance. Notice that these “hills” are on the big side. They’re only about 3000 ft high, but they’re as craggy and jagged as any alpine range. They dominate the skyline of most of Skye. I’d say they’re at least mini-mountains, yes? Can’t wait to go climb one.

We’ve relocated further south to be near the Cuillin Hills, shown here off in the distance. Notice that these “hills” are on the big side. They’re only about 3000 ft high, but they’re as craggy and jagged as any alpine range. They dominate the skyline of most of Skye. I’d say they’re at least mini-mountains, yes? Can’t wait to go climb one.

“Coire” is a Scottish (Gaelic) name for a cirque, an amphitheater-like basin gouged from a mountain by glaciers – see the first picture of the Cuillins a couple pictures above – the Sgùrr nan Gillean peak. To get to Coire Lagan we have to circle around the Cuillins, enjoying the views of the mini-mountains such as those shown here.

“Coire” is a Scottish (Gaelic) name for a cirque, an amphitheater-like basin gouged from a mountain by glaciers – see the first picture of the Cuillins a couple pictures above – the Sgùrr nan Gillean peak. To get to Coire Lagan we have to circle around the Cuillins, enjoying the views of the mini-mountains such as those shown here.

This last shot is of Sgùrr nan Gillean back at our Sligachan Hotel.

This last shot is of Sgùrr nan Gillean back at our Sligachan Hotel.

(2400 ft) mini-mountain on this peninsula, anchoring the southern end of the Trotternish Ridge. In particular we’re visiting the Old Man of Storr, that little spike of rock on the right side of this picture. During the landslides, the Old Man landed on its end; after much weathering it’s still a 160 ft high vertical chunk of stone. This picture of the Storr, by the way, is from a different day that was sunny. Today it’s overcast and gloomy, as you can see in the pictures below. However, even in these misty

(2400 ft) mini-mountain on this peninsula, anchoring the southern end of the Trotternish Ridge. In particular we’re visiting the Old Man of Storr, that little spike of rock on the right side of this picture. During the landslides, the Old Man landed on its end; after much weathering it’s still a 160 ft high vertical chunk of stone. This picture of the Storr, by the way, is from a different day that was sunny. Today it’s overcast and gloomy, as you can see in the pictures below. However, even in these misty

We’re nearing the end of the loop, here looking back at the village of Uig. Note, near the center of the image, the parallel strips of land with a house at the top. In the old days the land was owned by Scottish clans or English aristocrats who divided it into these crofts and rented it to tenant farmers who eked out a bare living. Today they’re privately owned plots, but their history is still visible.

We’re nearing the end of the loop, here looking back at the village of Uig. Note, near the center of the image, the parallel strips of land with a house at the top. In the old days the land was owned by Scottish clans or English aristocrats who divided it into these crofts and rented it to tenant farmers who eked out a bare living. Today they’re privately owned plots, but their history is still visible.

broad plain, but mountains beckon in the distance. As we enter a hilly region, we encounter our first coo, a hardy breed of shaggy, red-coated cattle that survives well in these hostile Highlands. With their long hair and rakish look they’re adorable! Not often one can say that about a cow.

broad plain, but mountains beckon in the distance. As we enter a hilly region, we encounter our first coo, a hardy breed of shaggy, red-coated cattle that survives well in these hostile Highlands. With their long hair and rakish look they’re adorable! Not often one can say that about a cow.