We’ll finish with Glasgow by showcasing the really old. The Glasgow Cathedral and nearby Provand’s Lordship are among the very few surviving buildings from Glasgow’s medieval period. The Cathedral is the oldest building; Provand’s Lordship is the oldest house. And the Antonine Wall? Never heard of it? We hadn’t either; it was the real northernmost wall (at least for awhile) that separated Roman Britain from those pesky Scots.

GLASGOW CATHEDRAL

The Glasgow Cathedral is a superb example of Scottish Gothic architecture, and the most complete medieval cathedral on the Scottish mainland. The first picture below shows the Cathedral as it looked in 1820 (from a watercolor, “The Saving of the Cathedral”); the following picture shows how it looks today (the front towers seen in the watercolor were

demolished in 1840 as part of a grand restoration scheme that was never completed).

The history of the Cathedral begins with the construction of a small wooden church around 550 AD when St. Mungo started a religious community. That structure was replaced by a stone church which was subsequently badly damaged by fire in 1136. The walls of the nave in today’s church, up to the windows, are from the rebuilding that took place in the early 1200’s; the rest of the Cathedral was built in the mid 1200’s. The Cathedral survived the Protestant Reformation relatively unscathed (as depicted in the first picture) not because the reforming mobs of 1560 were less zealous in Glasgow but because the organized trades of the city took up arms to protect it, the defenders outnumbering the attackers. The title “cathedral” is now historic, dating from the period before the Scottish Reformation.

The cathedral interior is impressive, with a roof made mostly of wood.

Below are more views of the interior.

The many ceiling bosses of carved wood are all different, beautifully done, and colorful (and difficult to get in focus), as shown below.

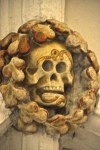

There are lots of interesting carvings in nooks and crannies throughout the cathedral (see below).

Another fascinating feature is the lower church beneath the Cathedral. The land on which the Cathedral was built slopes, which allowed a lower church containing a crypt to be built beneath the choir; the crypt contains the tomb of St. Mungo. It’s a large area, and

beautiful in a very different way than the soaring upper Cathedral. The stone bosses are also pretty cool, each one different.

Finally, there’s the beautiful Blackadder Aisle, built around 1500 on the site of St Mungo’s original church and designed to be part of a transept that was never completed (it’s hard to tell from the introductory pictures, but the cathedral has no true transepts). The beautiful,

stately, arching white ceiling is highlighted at intersections with very interesting and brightly painted carved stone bosses.

PROVAND’S LORDSHIP

This house, the oldest in Glasgow, was built by (and near) the Glasgow Cathedral in 1471. It likely reflects “the lifestyles of the rich and famous” for that time. It was originally the home of one of the 32 canons who managed a part of the Cathedral’s vast diocese – in this case the land at Provan (the other 31 canons were similarly housed). By the 1600’s it had become a private home; by the 1700’s, and for the next 200 years, it was used as an inn, with rooms on the upper floors and a wide range of shops on the ground floor. A small extension housed the city’s hangman. It’s a pretty cool place, all stone with massive, rough-hewn, low-hanging beams and fireplaces everywhere. The entrance opens into the

This house, the oldest in Glasgow, was built by (and near) the Glasgow Cathedral in 1471. It likely reflects “the lifestyles of the rich and famous” for that time. It was originally the home of one of the 32 canons who managed a part of the Cathedral’s vast diocese – in this case the land at Provan (the other 31 canons were similarly housed). By the 1600’s it had become a private home; by the 1700’s, and for the next 200 years, it was used as an inn, with rooms on the upper floors and a wide range of shops on the ground floor. A small extension housed the city’s hangman. It’s a pretty cool place, all stone with massive, rough-hewn, low-hanging beams and fireplaces everywhere. The entrance opens into the

kitchen – where it’s very obvious that cooking was not a big production! And of course a

dining room. The rooms upstairs are old-time, rustic gorgeous. The room shown below belonged to a canon from 1501 – 1513; he was both a priest and a lawyer. The room would have served as a living room, bedroom and office.

Other rooms are shown below.

Provand’s Lordship houses one of Scotland’s best collections of furniture from the 1600’s. The chairs below are examples.

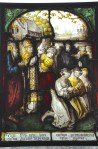

Provand’s Lordship also had medieval stained glass windows (now obtained from elsewhere). The windows below were from England in the 1600’s and commemorate marriages between notable families.

The window below shows 3 saints: St. Nicholas, St. Paul and St. Peter. It was made in the Netherlands in the 1500’s; the trefoil and 2 quarterfoil panels at the top are from England, made in the 1300’s.

The windows below are from the 1300’s. The left window has panels depicting an angel, St. John the Baptist (from France) and an unidentified female saint (from England). The second window depicts an unidentified male saint (from England). Strangely, there were no stained glass windows from Scotland.

THE ANTONINE WALL

What? Never heard of it? Interesting how history does that to us. Yet you’ve heard of Hadrian’s Wall, right? That northern-most demarcation of Rome keeping those pesky Scots at bay? Actually, that northern-most border was the Antonine Wall.

We discovered the little-publicized Antonine Wall when we visited a museum at the University of Glasgow; it’s a gorgeous university, as shown below.

Just for review, as noted in our Hadrian’s Wall post (Hadrian’s Wall), that wall was built in 122 AD; it was 73 miles long, went from coast to coast, and was built 15 – 20 feet tall from quarried stone (in the middle of nowhere), with 80 stone forts along its length. Probably as a result of continued attacks from  the unconquered north, in AD 142 Hadrian’s successor Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered a new wall built about 70 miles further north of the existing wall. Again these clever Romans somehow knew where the shortest distance would be, and the wall was built from the river Clyde just above present-day Glasgow to the Firth of Forth just west of present-day Edinburgh. The wall was 39 miles long, about 13 feet high, and 16 feet wide; it took 12 years to complete. It was built of turf and earth on a stone foundation. Like Hadrian’s Wall it had a deep ditch on the north side and a military road on the south. A wooden palisade is thought to have been on top. It was protected by 17 forts with about 10

the unconquered north, in AD 142 Hadrian’s successor Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered a new wall built about 70 miles further north of the existing wall. Again these clever Romans somehow knew where the shortest distance would be, and the wall was built from the river Clyde just above present-day Glasgow to the Firth of Forth just west of present-day Edinburgh. The wall was 39 miles long, about 13 feet high, and 16 feet wide; it took 12 years to complete. It was built of turf and earth on a stone foundation. Like Hadrian’s Wall it had a deep ditch on the north side and a military road on the south. A wooden palisade is thought to have been on top. It was protected by 17 forts with about 10 “fortlets”, very likely on (Roman) mile spacings. In spite of the effort it took to build the wall, it was abandoned only 8 years after completion (162 AD), the garrisons being relocated back to Hadrian’s Wall. Following a series of attacks in 197 AD, the emperor Septimius Severus arrived in Scotland in 208 to secure the frontier. He ordered repairs and re-established legions at Antonine’s Wall (after which the wall also became known as the Severan Wall). Only a few years later the wall was abandoned for the second time and never fortified again.

“fortlets”, very likely on (Roman) mile spacings. In spite of the effort it took to build the wall, it was abandoned only 8 years after completion (162 AD), the garrisons being relocated back to Hadrian’s Wall. Following a series of attacks in 197 AD, the emperor Septimius Severus arrived in Scotland in 208 to secure the frontier. He ordered repairs and re-established legions at Antonine’s Wall (after which the wall also became known as the Severan Wall). Only a few years later the wall was abandoned for the second time and never fortified again.

Apparently the ruins are not much to see; the turf and wood wall have largely weathered away. Still, the various legions that built the wall commemorated their finished construction and their victorious struggles with the natives (called the Caledonians) in decorative local limestone slabs, called “Distance Slabs”. The slabs were set into stone frames along the length of the wall. Dedicated to the Emperor Antoninus Pius, they identify the legion, the length of the wall they built, and with symbolic imagery they depict the might of the Roman army and the native population in defeat. In the largest known slab (shown below), the inscription reads: “For the Emperor Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius, Father of his Country, the Second Augustan Legion built this over a distance of 4652 paces.”

Other examples are shown below.

A number of stone statuary items from the bath houses and fort buildings attest to the Romans’ love of art even at their furthest outposts.

Other artifacts like coins and leather shoes were of course also plentiful.

That’s enough on Glasgow! Next post is a change of pace, on England’s Lake District.

art (stained glass, tapestries), Egyptian, Islamic and Chinese art, French Impressionist paintings, sculpture, armor, architecture, furniture…. Be prepared for ecclectic! So where to start, eh? How about this vase, found in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, from 100-200 AD (restoration in the 1700’s). Fill it with wine and take a bath?

art (stained glass, tapestries), Egyptian, Islamic and Chinese art, French Impressionist paintings, sculpture, armor, architecture, furniture…. Be prepared for ecclectic! So where to start, eh? How about this vase, found in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, from 100-200 AD (restoration in the 1700’s). Fill it with wine and take a bath?

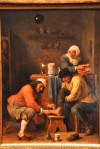

world. The 3 panels shown on the left came from a French cathedral from about 1280 (!), showing a wedding party in the center, with kitchen scenes above and below that referenced the trade guild that paid for the window. The only paint on the glass is a brown metal oxide that defines the faces, hair and folds of the clothes. The individual pieces of colored glass are small, and therefore the many lead canes holding them together made the panels strong. There are few restorations, and the window looks almost exactly like it did 750 years ago.

world. The 3 panels shown on the left came from a French cathedral from about 1280 (!), showing a wedding party in the center, with kitchen scenes above and below that referenced the trade guild that paid for the window. The only paint on the glass is a brown metal oxide that defines the faces, hair and folds of the clothes. The individual pieces of colored glass are small, and therefore the many lead canes holding them together made the panels strong. There are few restorations, and the window looks almost exactly like it did 750 years ago.

Our final look at a Mackintosh tea room is “The Willow TeaRooms and Gift Shop”. These rooms are not in a museum – they constitute a 1903 Mackintosh building that is still serving food and tea to the public. Below are pictures of these rooms as they looked in 1905;

Our final look at a Mackintosh tea room is “The Willow TeaRooms and Gift Shop”. These rooms are not in a museum – they constitute a 1903 Mackintosh building that is still serving food and tea to the public. Below are pictures of these rooms as they looked in 1905;

Actually, at least in spots it’s not all solid rock underfoot. Some exposed areas show deep layers of peat.

Actually, at least in spots it’s not all solid rock underfoot. Some exposed areas show deep layers of peat.

Nearby we spot another coo. Isn’t she cute??

Nearby we spot another coo. Isn’t she cute??

Our last topic is the amazing Callanish (Gaelic: Calanais) Stones on the west coast of Lewis. That aerial view to the left is a picture I took of a postcard. I would describe the site as a low ridge on which there is an arrangement of standing stones placed in a pattern of a cross, with the long arms oriented north-south, encompassing a central stone circle. Yeah, but that kinda misses the fact that they are 5000 years old and likely a focus for prehistoric religious activity for at least 1500 years (!). The ritual landscape was wider than this site; within a radius of 3 miles are 12 other standing-stone sites, a couple of them just visible from here. The stones were erected in the late Neolithic era, starting around

Our last topic is the amazing Callanish (Gaelic: Calanais) Stones on the west coast of Lewis. That aerial view to the left is a picture I took of a postcard. I would describe the site as a low ridge on which there is an arrangement of standing stones placed in a pattern of a cross, with the long arms oriented north-south, encompassing a central stone circle. Yeah, but that kinda misses the fact that they are 5000 years old and likely a focus for prehistoric religious activity for at least 1500 years (!). The ritual landscape was wider than this site; within a radius of 3 miles are 12 other standing-stone sites, a couple of them just visible from here. The stones were erected in the late Neolithic era, starting around

This is a last shot of the Isle of Harris. It is a pretty place. The next set of posts, and the last from bonny Scotland, will be from Glasgow with its fabulous Mackintoshes.

This is a last shot of the Isle of Harris. It is a pretty place. The next set of posts, and the last from bonny Scotland, will be from Glasgow with its fabulous Mackintoshes. Sleat is mostly flat, but it has great views across the water to the mainland (picture on the left). The series of pictures below capture Sleat nicely. They were taken from a single location, although the first picture was taken on a different day than the rest.

Sleat is mostly flat, but it has great views across the water to the mainland (picture on the left). The series of pictures below capture Sleat nicely. They were taken from a single location, although the first picture was taken on a different day than the rest.

This morning I’m greeted by the Sgùrr nan Gillean peak looking quite spiffy. It would be fun to climb that beast, but not this trip; I kinda doubt it’s a day hike, plus there would be mutiny.

This morning I’m greeted by the Sgùrr nan Gillean peak looking quite spiffy. It would be fun to climb that beast, but not this trip; I kinda doubt it’s a day hike, plus there would be mutiny.

the first picture above is called “The Needle”. As you can see in the other two pictures, we’re following the cliff wall to new mini-mountains up ahead. The trail is easy enough but it’s narrow, and occasionally when the hillside is quite steep, the downhill edges of the trail become a bit unstable. The trail shown in the left picture is less than a foot wide; walking across it is not unlike walking a gymnast’s balance beam, with consequences for slipping off.

the first picture above is called “The Needle”. As you can see in the other two pictures, we’re following the cliff wall to new mini-mountains up ahead. The trail is easy enough but it’s narrow, and occasionally when the hillside is quite steep, the downhill edges of the trail become a bit unstable. The trail shown in the left picture is less than a foot wide; walking across it is not unlike walking a gymnast’s balance beam, with consequences for slipping off.

I love this picture! The view is fabulous, but it also helps you appreciate the huge “sloping plateau” I’m on, which is very much like one to the far right in this picture, but much bigger.

I love this picture! The view is fabulous, but it also helps you appreciate the huge “sloping plateau” I’m on, which is very much like one to the far right in this picture, but much bigger. I’ve finally reached the top; this high up, there’s a commanding view, shown on the left.

I’ve finally reached the top; this high up, there’s a commanding view, shown on the left.

to a rural setting, and after traveling back and forth on a narrow winding road devoid of signs or parking lots, we decide that two cars parked at the edge of the road must mark the spot, and off we hike up some hills. Behind us in the distance is a pretty impressive waterfall!

to a rural setting, and after traveling back and forth on a narrow winding road devoid of signs or parking lots, we decide that two cars parked at the edge of the road must mark the spot, and off we hike up some hills. Behind us in the distance is a pretty impressive waterfall! and scrub trees, we begin to see a unique landscape of furrowed conical hills. The glen itself is a small secluded area – fitting for small fairies, right? It has a rocky pinnacle that will provide an overview, so up I go. The scramble is a bit precarious, with edges on both sides, and Ginger decides to explore from below.

and scrub trees, we begin to see a unique landscape of furrowed conical hills. The glen itself is a small secluded area – fitting for small fairies, right? It has a rocky pinnacle that will provide an overview, so up I go. The scramble is a bit precarious, with edges on both sides, and Ginger decides to explore from below.

Now on to the Dunvegan Peninsula! The roads here – like many of those on Skye – are one lane, making driving more interesting. Usually the roads are paved, but not always. And as shown in this image, I think “traffic jam” on this island means nose to butt sheep on the road.

Now on to the Dunvegan Peninsula! The roads here – like many of those on Skye – are one lane, making driving more interesting. Usually the roads are paved, but not always. And as shown in this image, I think “traffic jam” on this island means nose to butt sheep on the road.

We’ve relocated further south to be near the Cuillin Hills, shown here off in the distance. Notice that these “hills” are on the big side. They’re only about 3000 ft high, but they’re as craggy and jagged as any alpine range. They dominate the skyline of most of Skye. I’d say they’re at least mini-mountains, yes? Can’t wait to go climb one.

We’ve relocated further south to be near the Cuillin Hills, shown here off in the distance. Notice that these “hills” are on the big side. They’re only about 3000 ft high, but they’re as craggy and jagged as any alpine range. They dominate the skyline of most of Skye. I’d say they’re at least mini-mountains, yes? Can’t wait to go climb one.

“Coire” is a Scottish (Gaelic) name for a cirque, an amphitheater-like basin gouged from a mountain by glaciers – see the first picture of the Cuillins a couple pictures above – the Sgùrr nan Gillean peak. To get to Coire Lagan we have to circle around the Cuillins, enjoying the views of the mini-mountains such as those shown here.

“Coire” is a Scottish (Gaelic) name for a cirque, an amphitheater-like basin gouged from a mountain by glaciers – see the first picture of the Cuillins a couple pictures above – the Sgùrr nan Gillean peak. To get to Coire Lagan we have to circle around the Cuillins, enjoying the views of the mini-mountains such as those shown here.

This last shot is of Sgùrr nan Gillean back at our Sligachan Hotel.

This last shot is of Sgùrr nan Gillean back at our Sligachan Hotel.

(2400 ft) mini-mountain on this peninsula, anchoring the southern end of the Trotternish Ridge. In particular we’re visiting the Old Man of Storr, that little spike of rock on the right side of this picture. During the landslides, the Old Man landed on its end; after much weathering it’s still a 160 ft high vertical chunk of stone. This picture of the Storr, by the way, is from a different day that was sunny. Today it’s overcast and gloomy, as you can see in the pictures below. However, even in these misty

(2400 ft) mini-mountain on this peninsula, anchoring the southern end of the Trotternish Ridge. In particular we’re visiting the Old Man of Storr, that little spike of rock on the right side of this picture. During the landslides, the Old Man landed on its end; after much weathering it’s still a 160 ft high vertical chunk of stone. This picture of the Storr, by the way, is from a different day that was sunny. Today it’s overcast and gloomy, as you can see in the pictures below. However, even in these misty

We’re nearing the end of the loop, here looking back at the village of Uig. Note, near the center of the image, the parallel strips of land with a house at the top. In the old days the land was owned by Scottish clans or English aristocrats who divided it into these crofts and rented it to tenant farmers who eked out a bare living. Today they’re privately owned plots, but their history is still visible.

We’re nearing the end of the loop, here looking back at the village of Uig. Note, near the center of the image, the parallel strips of land with a house at the top. In the old days the land was owned by Scottish clans or English aristocrats who divided it into these crofts and rented it to tenant farmers who eked out a bare living. Today they’re privately owned plots, but their history is still visible.

broad plain, but mountains beckon in the distance. As we enter a hilly region, we encounter our first coo, a hardy breed of shaggy, red-coated cattle that survives well in these hostile Highlands. With their long hair and rakish look they’re adorable! Not often one can say that about a cow.

broad plain, but mountains beckon in the distance. As we enter a hilly region, we encounter our first coo, a hardy breed of shaggy, red-coated cattle that survives well in these hostile Highlands. With their long hair and rakish look they’re adorable! Not often one can say that about a cow.